“I’d like to make it clear that you talked me into this,” says Taylor Prestidge, pointing at me in the face with one hand, holding a pint in the other. “There has to be something in there that says that. I do all these things that are pretty public facing and outward, and people think that because I’m an outgoing guy…”

“You’re the lead singer of a rock n roll band,” I interject sarcastically, pointing back.

“That’s Franco Goldman, man – you’ll have to talk to him,” he responds with a smile. “Nothing makes me feel more out of my skin than accolades around what I do, because I truly don’t do it for that. I’m happy to do this because I know how lucky I am to get to do what I do for a living and I won’t take it for granted.”

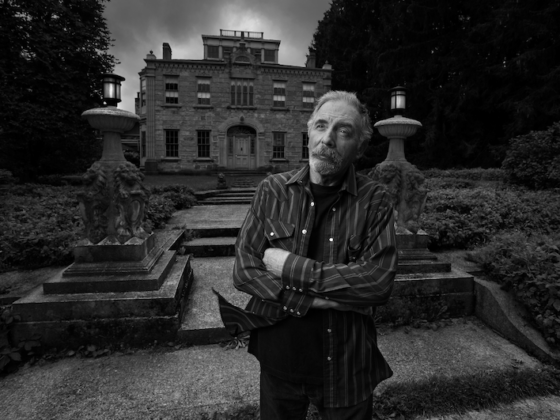

So who the hell is Franco Goldman, and who’s the guy responsible for the creation of an alter-ego capable of accepting his accumulating laurels of success? I’ve managed to twist Taylor’s arm into joining me for a chat – a loud, mullet-sporting, tattooed, multilingual hockey goalie that spends his spare time ‘training’ for the Scottish Highland Games, schmoozing with Canadian sports legends, moonlighting as a contributor for The Hockey News, graduating from Second City and touring barrooms as a stand-up comedian in his early 20’s, and singing in a goddamn rock band, The Tuesday Nighters. We met at our sons’ hockey practice, where he stuck out like a sore thumb having almost religiously worn an all-blue Winnipeg Blue Bombers velour tracksuit for the duration of the season on-ice as a volunteer coach.

Leading an interview with a pre-existing bias is never a good idea, but when that’s your introduction to a gent who repeatedly tells you they hate the limelight – the beer you’re sipping tells you to stick your neck out and call a spade a spade.

Originally from Milton and now calling Annan home with his wife and three young ones, Taylor’s a filmmaker with an impressive early resume. Focusing on documentaries centered around the origin stories of mental health for some of Canada’s most well-known athletes, his path to the director’s chair is a unique one. The focus for this story was originally set to be on 4-time Olympic gold medallist and IIHF Hall of Famer, Hayley Wickenheiser, after Taylor wrapped his latest film, Wick, here in Grey County about her storied hockey career – but after creeping the guy on the interwebs, it became clear his dedication to talking about adversity, mental wellness, equal opportunity, and substance abuse in sports should be the showcase – no disrespect to Captain Canada.

When you zoom out and look at athletes and creatives, it’s easy to paint them as polar opposite archetypes, but Taylor found a way early on in his career to blend the two and expose the individuality and creativity of sport, and the often overlooked physicality and team-based necessity within film.

“In high school I wanted to be the cool guy so I played on the football team, I played on the hockey team, and I played on the baseball team – but I also did the school play, hosted the talent shows, and was the Valedictorian – so I almost lived these two lives,” says Prestidge. “Guys that I play sports with have jokingly said I’ve been performing forever – whether it’s trying to sell a penalty or performing in the changeroom for the entertainment of anyone who will listen.”

Taylor was recruited to play CIS Football and simultaneously was accepted to journalism school when a best friend tragically passed in an accident just a month before he graduated high school. That experience was instrumental in helping him realize how short life can be, and how seizing every opportunity is key to leaving it all on the field, so to speak.

“That set me on a path I didn’t expect and I decided I was going to pursue the arts. I can still be involved with sports, just through a different lens. I was going to be a true-blue sports reporter, whether that was in print, on TV or the radio – though I didn’t have a voice for radio, I’ve been told I have a face for it,” he cracks. “When in school I took a documentary class where the entire curriculum was a study of Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man. I remember thinking, ‘wow, this is a different way of telling stories and performing and everything I’ve thought about, but it’s aligned with everything I’ve been learning.’”

The long form exploratory nature of the documentary really struck a chord with Taylor, who quickly identified with the element of performance and tenacity it takes to visually and emotionally articulate a story over time. He had the chance to meet and greet with some major sporting personalities, namely storied CFL athlete and now-friend, Andrew Harris, and longtime Toronto Marlies Captain and Leafs alumni, Rich Clune – two individuals who would become the focal points of his first two films, centered on overcoming the darkness that can surround athletes and can manifest as anxiety, aggression, and substance use disorder.

“I really wanted to make content that people could relate to, but take Hayley Wickenheiser, for example – she’s a doctor, gold medallist, competed in multiple Olympic sports – this super over-achiever – who the hell can relate to that? But what everyone can relate to is the struggles and the human side of who she is. With Dicky (Clune), the way he looks and playing in the National Hockey League, no one can relate to that, but him talking about disappointing his brother – bringing him to tears in the film talking about the shame he feels and what he put his brother through – every human on the planet can relate to feeling like they’ve wronged someone and be moved by that.”

His 2023 film, Wick, in particular is a stunning piece of work. Whether you’re a hockey fan or a fan of sports at all – the humanity that’s weaved into the 40-something minute film will turn even the most stone-cold viewer into an emotional shadow of their former self. I’ll explain:

I spend a lot of time at the rink as a father of two kids that both love the game. The sport found my daughter and she decided to lace ‘em up, at first, for the social aspect of the game. Now in her second year, she’s recorded her first hat-trick and can skate like the wind. Around the same time I watched Wick at the Grey County premiere in Owen Sound, my wife and I were considering pulling her from the odd tournament to save a few weekends, some money, and our sanity. In the film, Dr. Wickenheiser describes the adversity she faced as a young girl trying to play the game in western Canada; being scolded by parents and coaches for daring to try-out, called names by the threatened boys and their mothers.

The emotion of Hayley’s mom, tears running down her face, describing the feeling of watching her child take this unwarranted cruelty and abuse, struggling to play the game she loves – it completely changed my outlook on the sport as a new hockey parent navigating a taxing and challenging athletic landscape. After seeing what kind of hardships the most decorated and talented female hockey player the world’s ever known had to overcome, over my dead body would I deny my daughter the opportunity to play because I wanted a weekend back. If that doesn’t equate to a documentary masterfully executed, I don’t know what would. Eat your heart out, Herzog.

The inescapable pull to create art is a profound call to answer. Creating content in a world like this one is challenging enough as-is, and choosing to do it in a traditional long-form medium like documentary is even more gutsy, given the ever-shrinking attention span of global audiences wide-eyed for TikTok snippets. It becomes clear that Taylor’s ambition as a filmmaker – and as a human being – is rooted in a need to create; not just art, but opportunities, memories, and powerful impressions.

“First and foremost, I try to be a good dad and a good husband… [but] I still miss sports. I miss the camaraderie of being in the changeroom. You get it with film crews when you’re on the road, but it’s different. It sucks to miss my kids and family, but you do get that camaraderie. That’s why I do things like the Scottish Highland Games. Seeing the competition [in Fergus] I always thought it’d be fascinating, so rather than dipping my toe in the water, I thought ‘why not just jump the fuck in?’ In everything I’ve described, I have a moment where I’ve been like ‘I’m not going to do it, I’m uncomfortable,’ but putting yourself in positions like that is so essential to human growth and I really subscribe to that concept.”

It’s clear this is a guy whose legacy will be a digital chapter book of experience focused on treating yourself well and putting yourself out there, even when you don’t really want the attention that comes with it. Franco Goldman aside, his name deserves some firsthand praise – and I tell him that.

As the interview winds down we find the bar has closed, it’s a rainy Wednesday night and we both have families to get home to. There’s a lost-looking couple wandering about, hoping for the help of a server. Exploring the area from England and unable to book a cab, they’re stuck at the restaurant with no way back to their AirBnB in Balmy Beach – too far to walk without navigating a foreign place at night in the pouring rain.

“I’ll give you a ride,” says Taylor, gallantly.

Of course he will.

—

Photos by: John Challinor, Zak Jackson, and Sean O’Neill