This story begins with a father, Steward Madill, sending his son into a bush lot in the hills of Balaclava to see if its timber was worth the investment. The answer he received was noncommittal, so Stew took his Skidoo up the hill himself, eventually dropping it to follow some coyote tracks, which led him out to a stunning view of a bowl-shaped valley overlooking Georgian Bay. He bought the lot, never cut any timber and, along with running Markdale’s Dairy Daughter, set to work bringing a casino to Coffin Hill.

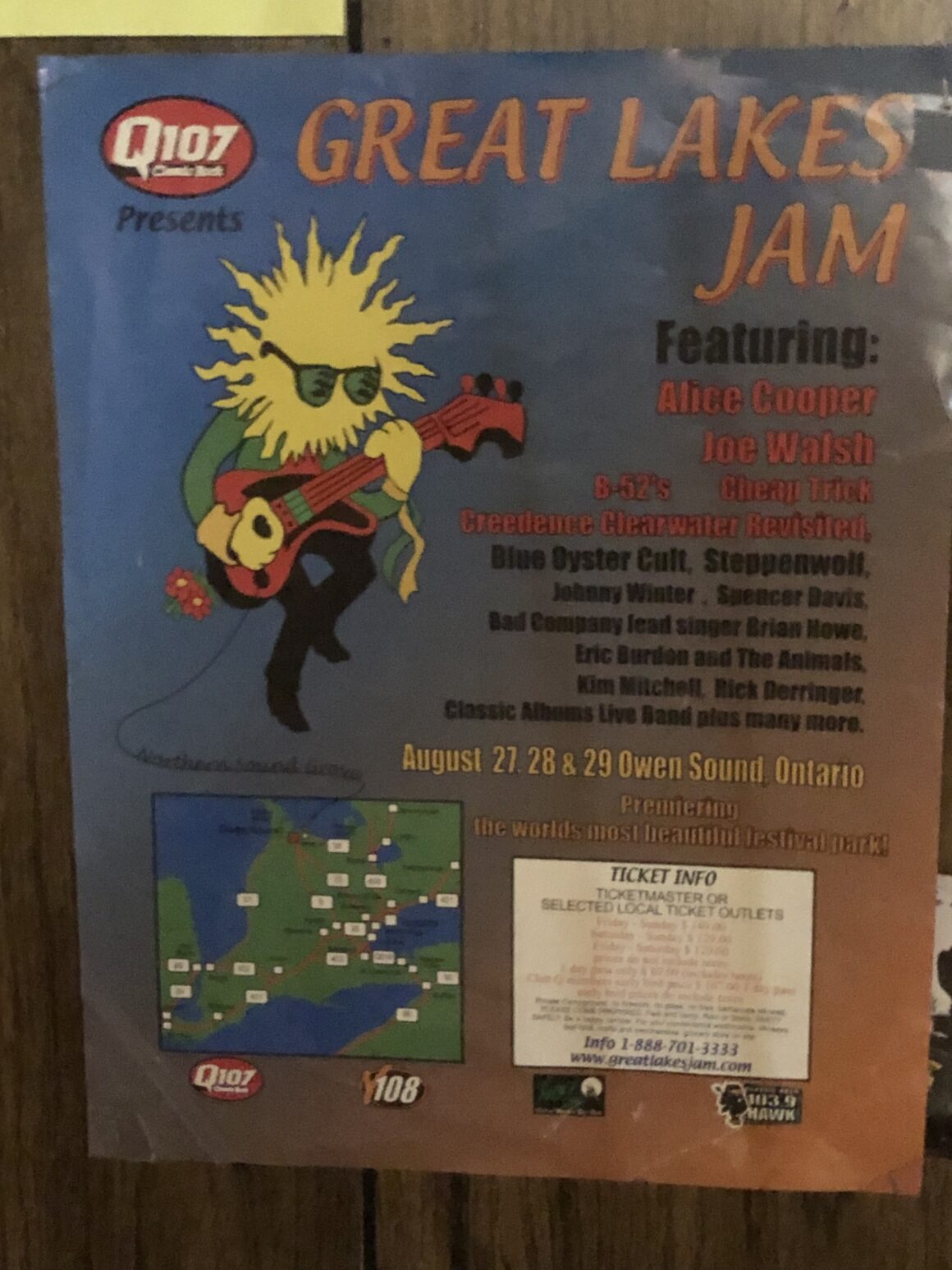

This made him a known quantity with the County, the Ministry of Tourism, then MPP Bill Murdoch and, eventually, in the case of the Great Lakes Jam, three Chinese investors willing to put up $2 million to stage a classic rock festival for 15,000 people.

After facing growing resistance, the casino bid eventually lost in a referendum and Madill shifted his focus from gaming to show business.

Bill Murdoch, no slouch when it came to organizing musical events on a grand scale himself, connected Stew with the head of Summergrove Productions, Wolfgang Siebert, who had decades of experience organizing big outdoor festivals. Wolf had worked with bands like The Specials, Killing Joke, Iggy Pop and the GoGo’s at Oakville’s Police Picnic in ’81, and hosted years of Carlisle Country Campouts, which, on one weekend alone, hosted Rickie Skaggs, Waylon Jennings, Charley Pride, Tammy Wynette, Buck Owens, and Carl Perkins.

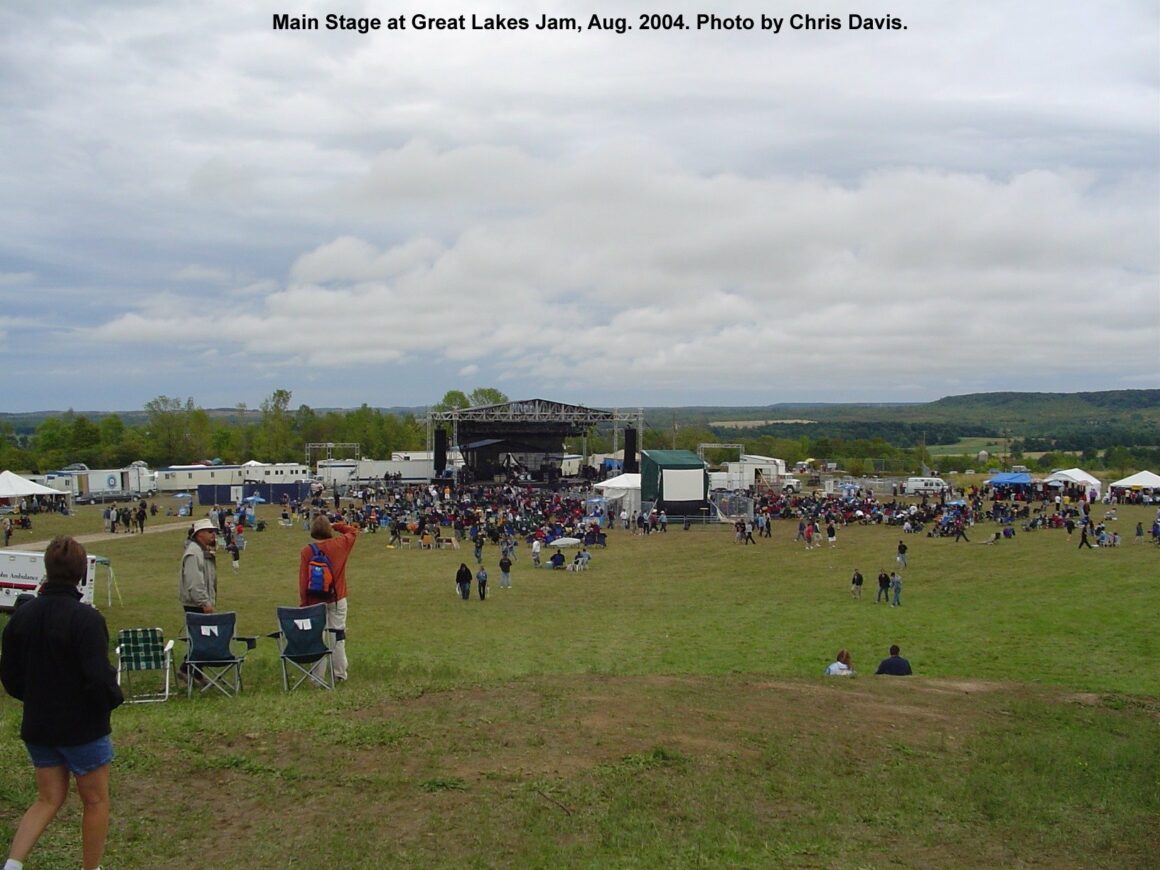

The magic ingredient in Wolf’s special sauce? A knack for laying out weekend festival sites for 25,000 people, and the firm conviction that the festival experience is vastly enhanced when it’s laid out in beautiful natural surroundings.

The paperwork was penned, Joe Walsh was taken on a fishing trip on the Bay, and big dreams were dreamt. One particular hope was that word of this beautiful area would filter back to Joe’s brother-in-law Ringo Starr. Stew got his heavy machinery to work laying out roads for the expected crowds. He spent three years getting permits and doing things right so that the space could host festivals year after year.

Agreements were in place for four years’ worth of productions. The plans were to host two events: one country, one rock, every summer at the new outdoor festival venue on Stew’s land. Even though Wolf and Stew had the support of Murdoch, the County, the Minister of Tourism, and sponsors who went so far as to take out a full page ‘Save Great Lakes Jam’ ad in the Owen Sound newspaper, a new mayor was elected in Meaford, who didn’t share the duo’s vision, putting up roadblocks, which scared off the international investors that, right after clean water and clean land, valued political expediency.

But for one glorious August weekend in Balaclava, live music was played by the likes of Spencer Davis, CCR, Alice Cooper, The B-52s, Cheap Trick, Kim Mitchell, Rick Derringer, Johnny Winter, Joe Walsh, Brian Howe, Blue Oyster Cult*, Eric Burdon & the Animals, Steppenwolf, and locals Tin Man and the Flying Monkeys.

From the audience’s vantage point everything around and behind the stage was Georgian Bay, meaning that from the right angle, the SARSstock-sized stage appeared to be floating on Mnidoo Gamii, Great Lake of the Spirit.

The festival kicked off with Rick Derringer, who, on top of penning Rock n’ Roll Hoochie Coo, worked with Steely Dan, Johnny and Edgar Winter, and produced Weird Al’s Eat It. Spencer Davis and Creedence Clearwater Revisited rounded out the first night’s bill, an evening three years in the making that festival organizers made sure the audience was ready for. Great Lakes Jammers were welcome to camp out for two nights before and after the event, making it an idyllic weeklong summer vacation.

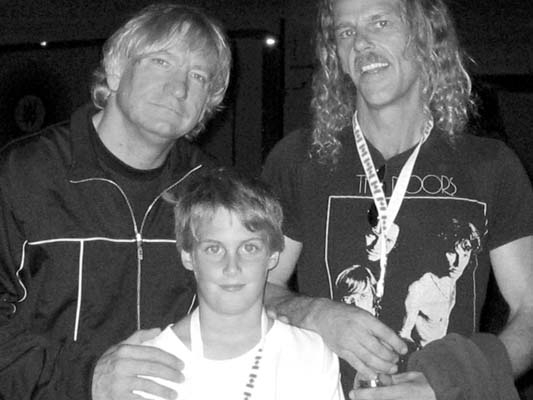

Beaker Granger, Martin Rice, Johnny Roy, and Stu Narduzzo, collectively known as Tin Man and the Flying Monkeys, stand out as being the only local band to rock the stage, opening the show on Saturday afternoon. The band is convinced Johnny put in seven miles running around that stage; Stu lived up to his reputation as THE flying monkey; Martin Rice had a nap before and after; and as for Beaker, it was quite simply “absolute euphoria.” The sound crew chief was a friend of the band and gave Tin Man Alice Cooper’s EQ – we’re talking 180,000 watts of pro audio! Between that experience and watching his kid wrestle with Joe Walsh backstage, it’s no wonder Beaker felt like he’d “made it for a day.”

Brian Howe was the opener on Sunday, but rain delays meant that the second act was shuffled off to play the beer tent. Blue Oyster Cult didn’t take kindly to that and got back on their bus. The BOC was the only band that didn’t take to the stage, a tragedy considering their song The Red and the Black, about the RCMP and covered by The Minutemen & Iron Maiden, would have been especially thrilling to hear on Canadian soil.

Alice Cooper was the last performer at Great Lakes Jam, bringing the nightmare to Coffin Hill. Sadly, for Stew, Wolf, and everyone involved in the Jam, the nightmare became a reality when the foreign investors pulled out. Legally, Great Lakes Jam was in the right and could have persevered through the roadblocks but the investors, who were hard to find considering the fest’s out-of-the-way location, lost their nerve when the variables began to multiply at the fledgling outdoor venue.

Tracts on this particular headland are back in the news due to TC Energy’s pumped storage plans. Stew has hung onto the land; the perfect concert bowl endures and next time you’re out at Coffin Hill in Balaclava, take in the view, appreciate the clean water and clean land that attracts both tourists and permanent residences alike, and listen on the wind for echoes of that magical weekend when rock rang out in Grey County.

Words by Tom Thwaits

Photos by Chris Davis