In 1253 Franciscan monk William de Rubruck journeyed 9000 kilometres into the heart of the Mongol Empire on behest of King Louis IX of France. His mission was to spread Christianity to the Mongols (or at the very least persuade them to stop killing so many Christians). His book, The Journal of William de Rubruck – Account of the Mongols, is today regarded as a masterpiece of medieval literature.

Upon first encountering the infamous Mongols, he wrote, “When I found myself among them it seems to me of a truth that I had been transported into another world.” I travelled to those same barren steppes in the fall of 2016 and again in 2017. Although seven hundred and sixty-five years had passed since Rubruck penned those words, I shared his sentiments.

Rubruck’s description of Mongol life back then paralleled what I saw: nomadic steppe people surviving as pastoralists, living in circular tents (gers), riding horses, heating and cooking with dung, enduring Mongolia’s extreme weather while constantly moving with their herds of yaks, horses, sheep and goats, to find stunted grasses for nourishment.

But it was a particular sub-set of their culture that really motivated me to travel there. These are nomads that also hunt wild animals, and it was their precise hunting method that I found so amazing: that is not with guns, or spears, traps or bow and arrows – but rather with huge golden eagles.

Worldwide, golden eagles are not endangered or considered even rare, yet they are seldom seen. They retain a distinct preference for locales that are void of people, making the Mongolian steppes prime habitat.

Ulaanbaatar is Mongolia’s only large urban center (almost half of Mongolia’s three million people live in Ulaanbaatar). From there I flew to the western corner of Mongolia – to the mountainous frontier amig (province) of Bayan-Ölgii – the only place where the tradition of hunting with golden eagles still occurs.

This area is dominated by the snowclad Altai Mountains making September and October weather equivalent to our early winter. For many nomad families, this means moving into more substantial stone and cement-walled structures. Some nomads, however, remain in their gers year-round.

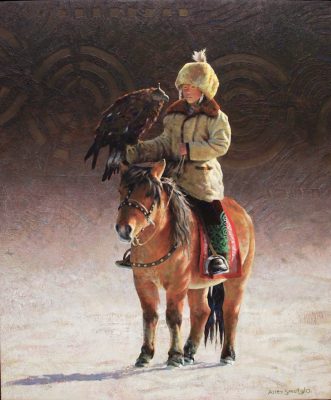

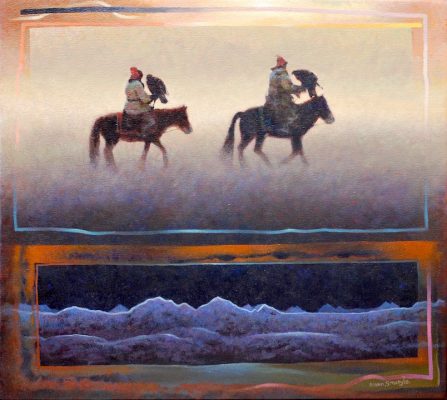

This is home territory of the Kazakh people, with their language, religion and customs differing from the rest of Mongolia. With an interpreter, I travelled around the territory, living with seven eagle hunters and their families. I also attended the annual Eagle Hunting Festival near the town of Ölgii. Like something out of Game of Thrones, 100 hunters, clad in wolf and fox fur, ride into the town from near and far, with enormous eagles on their arms.

The entire process of hunting with golden eagles is a time-consuming and highly complex endeavour. To start with, you need to find a wild eagle. Not easy when the bird has a strong preference to be where people aren’t. Taking an eagle from the nest is an option, provided the eagle has not completely fledged. This usually involves lowering a child and a burlap bag down a cliff face using a rope. If the eaglet you aim to obtain is too young, however, it will lack the internal wildness to become an effective hunter. Trapping with a lure or a baited device is another eagle-catching technique, but only a young eagle, one or two years old, will do – any older and the eagle will be too wild to train. After that, an eagle can take months to train, with its personality often determining the success of the interaction.

For hunters, female eagles are strongly preferred. They are more aggressive than males and 40% bigger, enabling them to take down larger game, such as marmots, foxes, wild sheep and goats and even, on occasion, 75 pound wolves.

The winter months is when the nomads hunt with their eagles, as the pelts and furs of the wild game are at their best. They will keep an eagle as a hunting companion for about 6 years, after which the bird will be released back into the wild to mate, helping sustain a healthy population (a golden eagle’s life span is 30 to 40 years in the wild).

Golden eagles can weigh as much as 15 lbs, with an eight-foot wingspan and a three-foot standing height. Apart from their size, the bird has some other impressive traits.

An golden eagle’s eyes can spot faint movement at a two-kilometer distance, and they can recognize 150 images per second (humans can comprehend 25 per second). They have both binocular and telescopic vision, able to flip from one to the other instantly. Also, they see colours humans can’t, inside the ultraviolet spectrum.

Most raptors are classified as specialists with singular or limited hunting methodologies. But the golden eagle is different; it is a true generalist. They have the problem-solving ability to calibrate their hunting methods to fit almost any prey in any area. Ornithologists have recorded golden eagles successfully hunting over 200 animal species in an array of habitats and climates.

And in flight, they can pursue prey at 300 kilometres an hour – faster than any animal on earth, apart from the peregrine falcon. Their claws are the size of a man’s hand, with talons that resemble abattoir meat-hooks, with the ability to exert 550 lbs pressure per square inch (an average person’s grip is 20 lbs per inch). By any measure, the bird is a spectacular killing machine.

*

The time and energy the nomads invest in obtaining, training and caring for their eagles is substantial – comparable, the nomads say, to raising a child. At first I wondered why, given the nomads already have an exhausting workload. When I asked one of the hunters I stayed with about this, he described his passion to hunt with his eagle as an addiction. Another referred to it as an obsession.

All of us have had at least some close interactions with a wild animal – be it simply a chickadee coming to eat seeds out of our hand at the bird feeder. No matter how brief or infrequent the incident, the moment usually leaves an indelible feeling of wanting more. I tried to compare those fleeting feelings with those of my eagle hunting friends. I tried to imagine having a huge apex predator, coming and landing on my arm when I called. And then, at a time and place of my choosing, sending it off into the wild to do my bidding.

It’s evident that this unusual bond between man and eagle goes well beyond facilitating a hunt for wild game (if the goal was hunting efficiency, they would simply use scoped rifles). This was conveyed to me by another nomad when he said it didn’t matter to him if a hunt was successful or not, he just cherished the time spent in the company of his eagle.

Governor General Literary Award nominee, Allen Smutylo, documents his Mongolian experiences in his new book; The Mongolian Chronicles – A Story of Eagles, Demons and Empires. www.allensmutylo.com

Images and words by Allen Smutylo