Is it normal to spend one’s holiday doing the two things they find the most difficult in life?

This past Christmas season, I left the mucous white Ontario overcast for the denim blue skies of Costa Rica to do two things: surf and write. And when I say they’re the two most difficult things I do in life, they’re also the most rewarding.

When I stepped off the bus and onto the marbled sands of Playa Tamarindo, I felt the warmth of the sun, and saw waters populated with tourists bouncing through waves, boards in hand, taking instruction from their hired surf coach. Then I was peed on by a monkey in the trees above me…but after that I breathed in deeply and knew I had made the right decision to go south for the holidays.

I was going to be one of those tourists for a day or two to get my bearings before moving onto a more difficult and out-of-the-way wave. It took three days to find one, but thanks to Mike, the poet surfer at Tamarindo Hostel, I found Langosta.

But let me back up a little and tell you why I went away for the Christmas holidays, a week I’m usually at home with family drinking rum and egg nog, napping on the couch, and reading all the books I’d put off during the year.

2018 had been a bit of a rollercoaster – mostly fun, a little scary, and definitely dizzying. I had someone beside me for most of the ride but when they moved to another country, I was on my own to close out the year. And that’s how I decided I’d spend my last week of December – solo. I wouldn’t have made a good travel partner for anyone anyways: I wanted solitude to start my second novel, and the freedom to grab my surfboard at the drop of a hat.

It didn’t matter where I went exactly as long as there was sun and waves. I knew I needed to get away for a week. I needed to not work. I needed to read a Franzen book. I needed to wander, to meet new people, to write a first chapter, to surf, to drink cold beer on a beach.

There is no better tasting beer than the one you have after a session on the water. Your muscles are sore, your spirits are high, and your thirst is unreal. You just battled Poseidon’s army of waves, took a solid beating, and walked out of the water in one piece. I mean, that’s one way to look at it. I did slice the inside of my mouth open spilling blood over the board; I did get my head knocked around and my body held underwater for longer periods of time than I’d choose to. I came close to breaking my hand.

But another way to consider surfing is the calm serenity that takes place after you’ve paddled out and joined the group of likeminded, but often fiercely competitive, surfers to vie for the grand form of that perfect wave.

The best wave heights around the area are in the afternoon after the tide comes in. I was up early on my first day, and just to make sure I wandered down sleepy eyed, coffee in hand to scope the swell at 7am, but sure enough the tide was out and there was nothing worth going out for.

This was fine with me: I could spend my mornings writing and my afternoons carving through the mighty right off Playa Tamarindo. At least for a day or two until I met a crew of expat surfers at Tamarindo Hostel. There was Mike, the Manhattan surfer poet; Chris, the Torontonian Great Lake surfer; Jamie the Aussie family man; Auda, the river raft guide and world wanderer; and Emma, the Sri Lankan gap-year girl. This crew was the one I’d spend most of my holidays with. I got to know Mike the best, who filled me in on Langosta. It was a twenty minute walk from Tamarindo, and known little by most tourists.

It was the best Christmas gift I got on this trip. I walked down there on Christmas Eve for the biggest swells I’d see the whole trip.

Once I made the trek down the road and through the discreet pathway to the sweeping beach split in two by a river head gazing out towards the sun at dusk, I knew I’d found my spot for the rest of the trip.

It was one of the best waves around with killer lefts and A-frames that rolled in from 3 – 6pm. And this was where the serious surfers came to carve and avoid the beginner to intermediate bracket. I am an intermediate, and it could be argued I should’ve left Langosta alone. They were protective of this area and didn’t let many visitors in on it. Mike had been there for three months and earned his spot. I had only been there for three days and I hadn’t earned a thing. But Mike trusted me after we spent a night at the hostel talking literature and comparing writing tips. I may have talked my surfing skills up a little with stories from Aus, Tofino, Montanita, and Barbados. I also gave him a copy of my latest book, which he seemed impressed by. Whatever it was, he put me in the know and I went the next day.

Initially, when I saw the calibre of surfers at Langosta, I was worried I wouldn’t be able to hang with the big timers. Even Tamarindo had it’s hierarchy – the Pickle was for the more experienced, while north of that was for the curious. I felt comfortable at The Pickle but something inside of me was pushing me out of my comfort zone.

I’d spent much of the year pushing myself out of my comfort zone, so it wasn’t too much of a stretch to do it in Costa Rica. There had been nothing more uncomfortable than publishing a novel for everyone you know to read. How many times did I second guess releasing it? What if people didn’t like it? What if they didn’t get it? I felt nervous every single time someone bought it or said they were reading it. It was unpleasant at times, especially the book launch. I pushed myself again by publishing a magazine, which was something very new for me. And there were times through the process when I didn’t think it would happen. There were many rejections along the way, which were hard on the spirit at times.

But it’s what I signed up for – there are risks and consequences to putting yourself out there. There always will be and if you dwell in the negative ‘what ifs’ then you’ll be ruled by them. And then there are no rewards. And having even one person take enjoyment in something you’ve created is definitely rewarding, regardless of how scary the process was.

I was nervous on my paddle out, I won’t lie. Hell, I’d been nervous to come on this trip in the first place, so it wasn’t anything new. I hadn’t traveled alone since Australia and forgot how challenging it can be at times. But once you get going and start meeting people, the nervousness falls away.

For anyone who has paddled out to join a lineup, he or she understands that there is a system at play, something that may be lost on spectators. To onlookers, it may seem as though a group of surfers is quite random. But there are rules, positions, etiquette, and order to a group of surfers on any particular swell, and if you want to belong, you have to understand it. I consider myself an intermediate surfer, but a respectful one.

I knew I was in the company of much better surfers and I paid careful attention not to fuck up my chance. As I paddled out on my first afternoon, I knew full well there would be eyes on the newcomer, and that my first wave would decide it. Either I’d catch my first break and show everyone that I belonged, or I’d bail and lose all hope of being given a serious turn in the lineup. The one advantage I had was that I’d been surfing the cold, messy, swells of Lake Huron the last month in a 5/4 wetsuit, so the warm, clean sets in nothing but a rash guard felt sublime.

I watched and waited.

I paddled for a few waves but yielded to those in position. I wasn’t in any hurry. I wanted the right one, something I could handle but something with enough power to take me all the way to the river mouth. I’m a goofy foot, but I like being backside to the wave, so the long lefts that were rolling out weren’t my favourite, but when a wave that William Finnegan would describe as ‘two refrigerators high’ was breaking too late for many at the top of the lineup, I knew it was mine for the taking. I paddled hard, gave a hard scissor kick and caught it.

I had no one to compete with or yield to. Just me. I could feel thirty pairs of eyes on me from behind as I arched my back and leaned upwards, pulling my body into position on my 6’9” Rusty and dropping in with mediocre form and abundant confidence. I was shot down the wave face with the force of the Pacific ocean, and held my stance as I dropped into it and glided along its unforgiving break. I got comfortable; I’d harnessed it. But eventually, it closed out in the middle before I could reach the river mouth. I knew it was enough, though, to get a nod when I paddled back out.

It was enough to earn my spot.

The reward was worth all the nerves that led up to it. I felt great! I was like Mikey McDee in Rounders after he plays at a table with Jackie Chan and walks away knowing he can sit with the best and play. I knew I could play with the Langosta crew and hold my own. They would become my family over the holidays and I would only learn one of their names.

It was where I spent the next four days surfing until the sun went down, and when you’re out on the water that much, you have a lot of time to think. Sometimes I sat in the back of lineup for long periods to watch the movements of the ocean and ponder life. There’s something about the sun on the horizon that always prompts reflection for me. It gave me time to attend to all the strands in ol’ duder’s head. It brought one of those moments of clarity that comes around every once in awhile.

Sure it was a strange feeling being on a board instead of sitting around a tree with your family drinking egg nog and recounting the year, but I’d had many of those and it was time for something new, something more selfish. Rilke famously says ‘You must change your life’ and it’s a powerful statement because change is difficult. It’s easy to keep doing things the same as you’ve always done them. But for anyone who is interested in growth, it takes making changes, and accepting all that comes with it.

While I watched adroit face carving efforts coming off A-Frame peaks in the Pacific on Christmas Eve I thought about a few things. I thought about the characters in my new book; I thought about the ups and downs of the past year; I thought about how cold it was back in Canada, and I thought about plastic.

I thought about the water around me and how it was slowly becoming overrun with a toxic product we’ve been tossing into it for a hundred years now. It didn’t seem possible that this vast body of clean water was filling up with garbage to the extent that there’d be more plastic than fish by weight in 2050. It didn’t seem real. And why did I worry so much when so many others didn’t?

I attempted a plastic free month in November and it was very hard. It made me realize how fucked we all might be because plastic really is everywhere. You realize it when you try to go without it. It’s hard work being conscious all the time – you’ve got to be on the ball constantly when making purchases. If you lose focus for a minute, someone will hand you plastic that will only be useful for an hour. But my month of increased consciousness meant that I noticed things I haven’t before; I was more aware; I was more awake. There is a benefit to that.

I had been doing so much reading the past few years and I think I got to a point where I had to stop reading and start acting. I think we’re in a post-discussion era now. It’s time to put the articles down and start doing things. There are many things I do that are detrimental, like flying, but I know I can take small steps like reducing plastic. It’s something I can do to start.

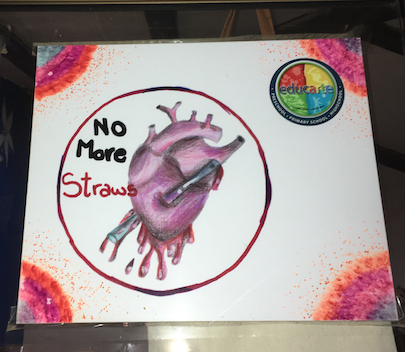

I had read that Costa Rica was taking steps to become more plastic and carbon free. I didn’t find it to be that exactly. They don’t have a recycling program and I didn’t see any renewable energy sources or electric cars. But there were glimpses of hope from time to time, like the following sign, my favourite for its graphic nature.

Another thing I spent a lot of time thinking about was how to find balance in life. What did it look like for me? I had let stress overwhelm me at times in 2018 because I lost my balance. There is a way to live life for everyone individually. I don’t believe in a one-size-fits-all meaning, so I’m careful to take advice or look to other people’s lives, but I do notice what seems to make others happy and find what’s applicable. I only know that I have to find times to stay in my comfort zone where I can relax and be myself, but also keep pushing myself out of that comfort zone to see what I’m capable of or missing out on. Sometimes there will be a reward, like Christmas Eve in Langosta, or an email from someone I barely know telling me how much they enjoyed my book, or the feeling I get returning home from traveling with a little more clarity. And sometimes there will only be discomfort, and that’s fine too. I’ll learn from it.

The key for me to be happy is to keep doing the things that are most rewarding. I don’t feel particularly talented at any of the things I do but I work hard and I dedicate time. The two most difficult, yet rewarding, things for me are writing and surfing.

Surfing is just plain hard on the body. It’s exhausting to paddle against waves; you duck dive under them but they still push you back. It never ends because every wave you take comes with a paddle back each time, but you know that going in, and you just decide to get better at it. You become stronger. And even when you’re going in the same direction as the waves, they can still be your enemy and hold you down and throw your board back at you, cut you, bruise you, scare the shit out of you.

But I wouldn’t do it if the reward wasn’t worth it. The thrill of riding a big wave is one that gives me chills every time.

Writing is a mental exercise that takes acuity, discipline, and creativity. It’s an activity riddled with anxiety and self-doubt, but there is a reward to putting yourself out there time and time again. We all have our way of doing this. We know it by our drive to get better at it. Because I’ve worked hard to get better at writing and surfing, I recognize them as important elements in my life.

We all have them. Those are just my two. And in Tamarindo on Christmas, I got my fill of both.

Written by Jesse Wilkinson