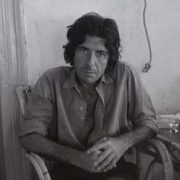

“Leonard Cohen is the only reason my husband gets laid some days” is what my Canadian Lit prof told us when I studied him in my undergrad. I never forgot that statement, one that revealed just how powerful his words and his music could be – how sexy he could make people feel with his voice.

I was already familiar with his work when I studied him in my early twenties. I had pulled his books of poetry off my parents’ book shelf as a kid and pored over his lines, drawn in by the overt sexual references and cryptic lines of The Spice Box of Earth and Let Us Compare Mythologies. I read The Favourite Game as a teen and fell in love with his prose. He kept popping up in my life at important times and leaving indelible marks.

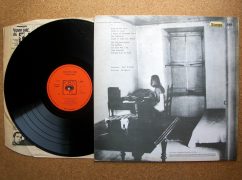

It wasn’t until my mid-twenties that I really got into his music. I was renting a cottage on the water one winter to write. I replaced the TV with a record player and played Songs From a Room every night and tried to write like him. It didn’t work. I just ended up putting the pen down and listening to his intoxicating, smoky voice spilling lines rich with metaphor, allusion and symbolism. Then I bought more of his records and wrote even less.

It wasn’t until my mid-twenties that I really got into his music. I was renting a cottage on the water one winter to write. I replaced the TV with a record player and played Songs From a Room every night and tried to write like him. It didn’t work. I just ended up putting the pen down and listening to his intoxicating, smoky voice spilling lines rich with metaphor, allusion and symbolism. Then I bought more of his records and wrote even less.

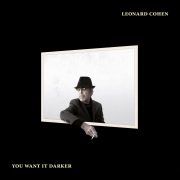

But this article is not about his life; unfortunately it’s about his death. I learned of it from a friend last night as I was out. It took me by surprise at first, until I got home and put on his recent album again. On a third listen, it hit me: this was his negotiation with death, whether he knew it was coming or not. The cause of death was not released and so it is difficult to argue this was a final goodbye, but the album is filled with metaphors of mortality, allusions to religion, and references to resignation.

This album was not for us. It was for him. He is not talking to us; he is talking to a higher power. When he talks about love, he is not talking about the love of a woman, as he has so often in the past. He is talking about a higher love, an eternal one.

And it’s not to say he hasn’t referred to religion in his songwriting before; he’s always been fascinated with it, whether it be a facetious line like “It’s dead as heaven on a Saturday night” from Closing Time or the poetic “You held onto me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark” from So Long, Marianne. But on You Want it Darker, he is talking directly to God. This is conversation we are merely eavesdropping on.

The album opens with a church hymn followed by a declaration that “If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game.” This sets the tone for the rest of the album as he then alludes to the crucifixion of Jesus and claims ‘There’s a million candles burning for help that never came.” He might be ready to go into the darkness and ‘kill the flame’, but he is not going gently into that good night. He has one more conversation to have, one more argument to make: that belief in God “seemed like the better way” at one point, but “it’s not the truth today.” He tells us this behind an eerie violin before arguing it’s “too late to turn the other cheek.”

Most people find God as they are nearing death; Leonard Cohen seems to do the opposite here. He is declaring his lost battle with religion, or at least one form of it; he has engaged with Judaism, Christianity, and Buddhism in his life but seems fascinated with only Judaism and Christianity here.

On Treaty, he declares his struggle with Jesus, one he has been fighting his whole life but seems to have clarity on now. He is too angry and tired to continue the fight and begs “I wish there was a treaty we could sign.” He then both repents and clarifies to say “I’m so sorry for that ghost I made you be/ Only one of us was real and that was me.”

Whether or not he thought death was coming soon, there are many hints that he has resigned to it on this album. On Leaving the Table, this feeling of resignation is at the forefront. “I don’t need a lover, so blow out the flame” he says “I’m leaving the table, I’m out of the game”. The constant references to ‘the game’, ‘the dealer’, and ‘the flame’ on this album may refer to love, but coupled with the constant reference to religion, it is fair to take it as a reference to life.

He tells us later in the album that “I’m running late, they’ll close the bar” inferring that he’s lived longer than he expected. He’s worried heaven won’t let him in, or hell, depending on your perception of a bar, but he’s being facetious – he doesn’t believe in either heaven or hell. He told us in On the Level that “I turned my back on the devil/ I turned my back on the angel too.”

But wherever it is he’s going, he’s Traveling Light. ‘Au revoir’ he sings on this one. Goodbye Leonard Cohen. Thanks for bringing so much to this world, to my world; you made it more interesting, more cerebral, a little classier, and little sexier.

Thanks for letting us listen in on your final conversation, one that is seemingly understandable with all your allusions to light and darkness, justice, card games and the Bible, but still with hints of paradox and obfuscation. “If you want it darker, I’m ready my Lord” is a line that could refer to the flame that extinguishes each time someone dies. Every life is a light. And if that’s the case, the world is a much darker place without you in it Mr Cohen. Your flame was bright – brighter than most.

Written by Jesse Wilkinson