Growing up in Owen Sound and loving TV, movies, photography, and books as much as I did – it was inevitable to latch onto a few names. For the past 15 years, I’ve had a list of people in the back of my mind with whom I’ve always wished I’d get to know, or even work with someday; Willy Waterton is on that list.

The man has profoundly influenced the graphic consciousness of our region, working for three and a half decades as the chief photographer at the Owen Sound Sun Times during a wildly adaptive time period that saw the transition from black and white 35mm film, to colour, then finally into the digital sphere.

His newspaper photographs have won well over 100 provincial and national awards, and back in 1990, Waterton received the distinction as the Ontario News Photographers’ Association Photographer of the Year. His work has appeared all over the world, in respected publications like National Geographic, the Globe and Mail, and the New York Times.

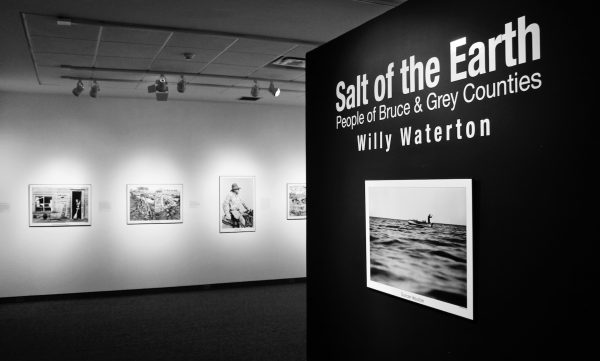

I had the opportunity to meet Willy for a one-on-one tour of his most recent exhibition, Salt of the Earth: People of Bruce and Grey Counties at the Tom Thomson Art Gallery. 192 people attended the exhibit’s opening in January, setting a new TOM record. The artists’ talk the following day was greeted by a standing-room-only crowd, so if you haven’t been and you call yourself a local – you need to hustle down there and take it in. The show is nothing short of bewitching – a true masterpiece of withering local culture and epic rural sagacity.

Salt of the Earth is set up in chronological order, sourced from the many, many boxes of Willy’s archived film negatives. Some of which he’d forgotten existed, others were welcome reminders of friendships and experiences out in the land.

“These were all part of longer-term projects. Going to the Cowboys, for example, that’s just one photo from a summer I spent photographing the Community Pasture. I went over in the spring and went through to the fall – and it was the same with the apple pickers and the fishermen… It evolved from BALL (Bluewater Association for Lifelong Learning) who do talks down at the Bayshore every Thursday. I was asked to do a talk as part of the photography series… I thought a lot of those people decided to retire in the area and y’know what? They really don’t know about this. This is an interesting way to combine photography, teaching, and the history of Grey and Bruce.”

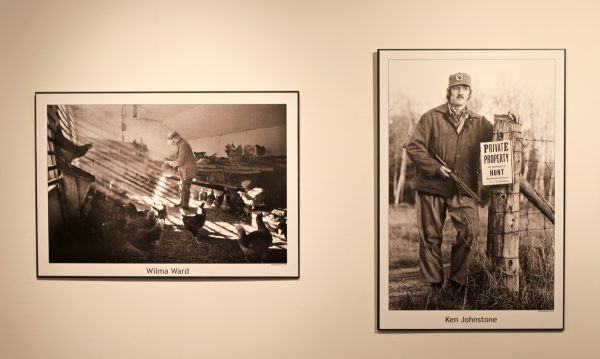

The show begins in the 1980s and features ample portraitures – but it’s a non-traditional approach to the medium – it’s heavily centred around environmental consciousness, and holds the same air of perceptiveness and freedom I remember impacting me as a young photographer and a fan of his work.

“I’m self-taught, so I don’t really have any rules to break,” says Willy. “I’m bound by the history and traditions of photography, but this photo [of Bill and Gert Mackie] for example… I went to their place and their orchard, and you can’t pose what they did… You can see in her eyes the love for it. It’s nontraditional in the sense you’ve got trees growing out of their heads, which is a no-no – but because they planted the trees, I felt the trees are growing from them.”

This is experiential photography through and through. Like a method-actor or an investigative journalist, Willy’s gift stems from the ability to build trust and relationships with his subjects – sometimes taking entire seasons or years to get into spaces of immense personal respite that showcase the fleeting cultures and eclectic nature of rural people.

You can sense Waterton’s love for the land in his photography. The variety of shots ranging from silhouettes, candid action shots, portraits, and landscapes are elevated by meticulously developed analog qualities like graininess from old school high ISO film, scratches, and boosted contrast, helping the drama and authenticity of each shot to shine through. And then you start to realize the time and energy it’s taken to document these things. And then, you start to understand the profound impact this dedication can have on the landscape, both culturally and physically.

Take for example Willy’s photo of a Bruce Peninsula couple, Edith and Cecil, who were being evicted from their generations-old family cottage on Emmet Lake in the late 80s, located in the modern-day Bruce Peninsula National Park.

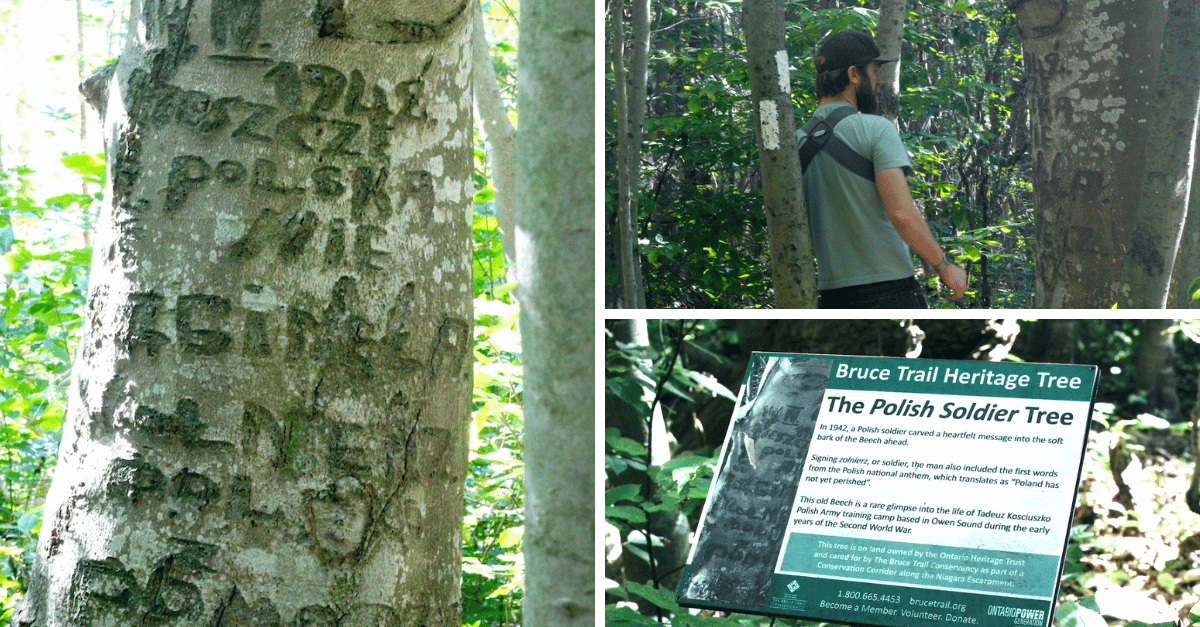

“The backstory is amazing. Edith’s family had cottages down in Point Pelee – and they got thrown out of Point Pelee National Park! Think of the chances of that! So we went up and we shot photos and did a story that went across Canada and as a result, Parks Canada very wisely gave them a life-lease so they could stay. It made perfect sense because they were basically stewards of the lake… We ended up becoming good friends with them and we’d go visit them up until their deaths. I was up there two years ago and I took a photo from the same place and there’s nothing there. It’s all been demolished… I believed – and I still do with some of my new projects, is that I’m a visual historian. This is a slice of time and place.”

The rise of photographic accessibility in the modern age coupled with the constant stream of content uploaded onto multiple digital channels can overwhelm the viewer to a point where photography is watered down to an ocean of meaningless snapshots. As a result, we sometimes forget the position and the vision of the photographer.

Taking great photos starts by putting yourself in front of great subject matter – and Willy’s work is a masterful example of this; but it’s his ability to make viewers recount his presence as well, that sets it apart. His spirit is embedded in this collection and that makes it special beyond comprehension. To amass work of this caliber, and of this particular subject matter means countless hours of talking, hiking, driving, learning, shooting, developing, and trusting — and you feel that dedication in the gallery.

“That’s the other thing that’s really important to me about this show: the photos were taken here, processed here, printed here by Parsons, formatted by Geoff Taylor (Foto Art’s Custom Lab printer) and plaque-mounted at Rockford – so this is a totally local product.”

Willy’s photography has both changed and protected the historical memory of our region and even physically altered the course of development in some of our most cherished natural environments. Salt of the Earth is defined as “an individual or group considered as representative of the best or noblest elements of society,” and when you walk around the exhibit, you get a sense of the monumental – and subtle – contributions these people made to the fabric of our local societal landscape.

“Some [subjects] were very off-handish. They did not want to be photographed, so it also took a long time to gain their confidence to allow me to photograph them,” says Willy.

“When I was a kid I grew up on a farm south of Rockford, and the next door neighbours – one of the fellows spent the summers living in the barn with his horses. There were just people like this around – they weren’t really eccentric – they were just normal, and I think we’re losing that. But they’re also people of the land… they’re elegant… Salt of the Earth describes them perfectly.”

I’d argue it describes Willy, too.

The Tom Thomson Art Gallery will be actively touring this series of powerful photographs throughout Bruce and Grey Counties, thanks to generous funding support from the fine folks at the Community Foundation Grey Bruce. The exhibition is slated to appear aboard the MS Chi-Cheemaun in 2019, then to the Bruce County Museum & Cultural Centre in the fall of 2020. TOM Curator, Heather McLeese, adds the show will also appear in local hospitals this coming fall.

Words and photos by Nelson Phillips